Retirees Need Mostly Stocks - Here’s Why

Most households are advised that their portfolio should become increasingly bond focused as they age. This belief, which has been passed down from generation to generation, is an attempt to create a pragmatic approach to ensuring you never run out of money. Portfolios like the 60/40 are a classic example — a typical advisor tells a retiree to put 60% in stocks and 40% in bonds. Another common example is the target date fund in 401k plans, which increases bond allocation as the target date gets nearer.

I am of the firm belief that these types of strategies are actively harmful by limiting total wealth creation and potentially adding more risk than is otherwise desired. I am going to walk you through my rationale and show you how I make more optimal solutions for retirees.

Defining Risk

To start, let’s break down the word “risk.” Risk is brought up anytime investments are being discussed, and how it’s defined is a significant component to allocating money successfully. Many academics and MBA earners are going to equate risk to volatility; that is, risk is the measure of how much a particular investment’s price moves in a given day.

I don’t think of risk as volatility, and neither should you.

I think of risk as the actual measure of an investment’s underlying strengths and weaknesses; that is, how likely is to make us money versus its ability to cause permanent loss of investment. This isn’t an easy thing to calculate because it requires fundamental analysis at its core and qualitative predictions of the future at its boundary lines. Nonetheless, a talented advisor will have the wherewithal to perform this analysis for you.

Bonds v. Stocks

Bonds are debt offerings by a company. When you buy a bond, you are lending your money to a corporation, who in return pays you interest with a lump sum due at maturity. You do not receive ownership in a company when you buy a bond, so you only care about getting paid back. Bonds therefore have more limited ability to create wealth and are handicapped by inflation. Bond interest is also taxed at higher rates than stock dividends.

When you buy stock, you are buying a piece of ownership in a company, called equity. Your participation in the increase in the company’s value is the primary reason to buy stocks. While you are last in line to receive a payout if the company goes bankrupt, you have theoretically unlimited upside in wealth creation and therefore are significantly more insulated against inflation.

Stocks are believed to be riskier because they are typically more volatile due to their tie to the company’s current value. As discussed above, that means their prices tend to move around more than bonds from the same company.

The most notable difference in terms of stocks and bonds is in potential wealth creation. Poorly picked stocks are probably just as bad as poorly picked bonds, but a well-picked stock has positive impacts to wealth development that even the best picked bond can’t compete against.

Why Bonds Change in Price

The initial rate offered by a bond is typically determined by the credit quality of the issuer; a riskier company will typically offer a higher rate. Once a bond is issued, its market value is primarily dictated via buying and selling in the market, which is heavily influenced by current interest rates and time to maturity. Bonds maturing later are more sensitive to rate movements while bonds maturing in the near future become less sensitive to rate movements. This concept, known as duration, requires a well structured bond portfolio to hold a varying mix of credit quality and time to maturity.

Why Stocks Change in Price

Like bonds, stocks only move because of buying and selling activity, called trading. Stock trading is driven by the difference between price versus perceived value. Investors who believe a stock is worth more than its price will buy it while investors who believe it’s worth less than its price will sell it. While valuing a stock is an incredibly complex and often imperfect task, buying and selling, regardless of reason, solely drives stock prices.

Reasons People Prefer Bonds With Age And Why They are Wrong

At the heart of every heavy bond allocation is a fundamental fear that stocks are more likely to cause permanent loss of life savings in a bear market, forcing a retiree back into the workforce. This bias to protect gains by limiting risk is known as Prospect Theory. Let’s break down where some of this fear comes from as it relates to our stocks v bonds discussion, and why I think there are way to advise around it.

(1) Sequencing: the misunderstood risk factor

Sequencing refers to the order of financial scenarios that play out in your life. For example, a new retiree who benefits from repeated years of 20% market returns is going to have a very different experience than a new retiree who suffers repeated year of 20% market declines. Sequencing is nothing more than good or bad luck, but it’s exacerbated by poor financial planning. It’s also worth nothing that if you aren’t withdrawing from your investments, you are immune from sequencing because you have runway to recover from any paper losses you’ve incurred.

To avoid sequencing risks, it’s imperative to first have a draw-down schedule for living expenses already set up for the first 3-5 years and second to wholistically invest for long-term success. This is something a talented advisor can and should be doing for any household that is at or nearing retirement.

The biggest misconception with sequencing is that bonds always protect against bad sequences more than stocks do. This could not be further from the truth. In the 2022 stock market crash, long-term bonds collapsed 30% while stocks collapsed only 20%. Furthermore, stocks fully recovered by December 2023 while long-term bond prices are still near all-time lows. For a newly retired investor in 2022, a 60/40 portfolio would have caused a permanent loss of capital, which based on our risk definition above, is the absolute number one thing we are trying to avoid.

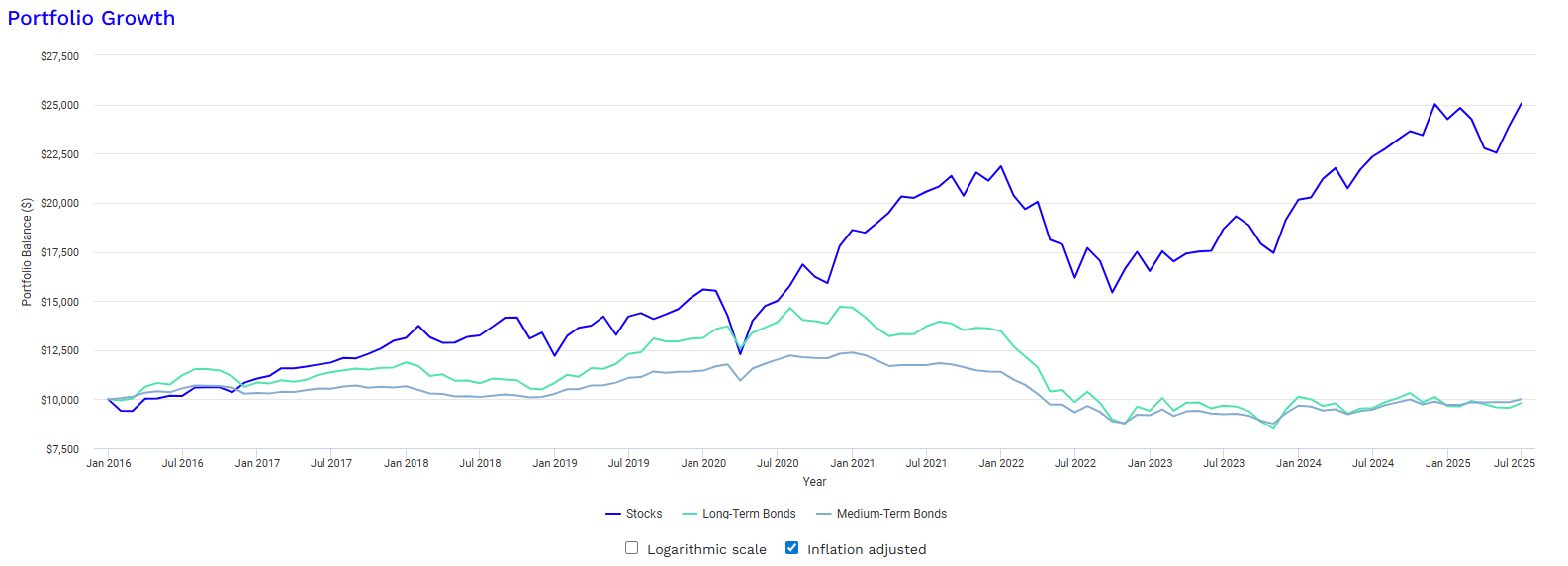

To illustrate the importance of being immunized from sequencing risk, the chart below shows a roughly 10-year run comparison of $10,000 invested in (1) stocks, (2) long-term bonds, and (3) medium-term bonds. The total return per year, including dividends and interest, is almost 14% for stocks and just 3% for bonds. You can see that the total value created from stocks (+$24,000) is more than 7x the value created from bonds ($3,300); thus, any retiree should try to be as heavily allocated to stocks as possible. The role of the advisor is to help make sure that is possible while keeping sequencing risk to a minimum. A 70/30 or 60/40 is far too conservative to achieve this objective and does a disservice to the client by reducing total returns unnecessarily.

(2) Inflation Underestimation:

Most retirees understand their bond portfolio to be one that has a steady and known return, which therefore limits their total downside risk (aka the real reason they avoid stocks). However, the primary flaw with this belief is turning a blind eye to a bond portfolio’s enemy #1: Inflation.

Inflation is tricky because it does not get measured when looking at an investment in isolation. To calculate an investment’s actual past performance, you have to look at its real return, which takes into account growth relative to spending power. In the graph below, we are comparing the same scenario as earlier but this time measuring total real return (i.e. including inflation). Notice how the bond portfolios are unchanged over nearly a decade while the stock portfolio has 150% more purchasing power than before.

(3) Risk-Reward: As we’ve discussed, many households believe bonds are inherently safer because they have known payments and are not tied to a company’s value (so long as the company stays in business long enough to pay the bond). The irony here is that because bond values have a fixed maturity value, their downside risk is actually more pronounced. In other words, you are taking on more risk relative to the reward when you choose bonds.

In financial economics, we can actually measure this phenomenon through a concept known as the Sharpe Ratio. The Sharpe ratio is a measure of return divided by risk. You want the highest Sharpe ratio possible because that means you’re getting the most return relative to the risk taken.

In our scenario set above, these are our Sharpe ratios:

Stocks: 0.76

Long-term bonds: 0.14

Medium-term bonds: 0.21

The relative comparison of the above numbers speak volumes. You are getting the 5x the return relative to the risk taken when you choose stocks over long-term bonds.

Scenario Set - Revisited

Throughout this article, we have drawn upon a decade long comparison of stocks, long-term bonds, and medium-term bonds. This decade included a number of major market events, such as the low interest rate run from 2010-2022, Covid, and the increase in rates in 2022. The table of values from that scenario shows that:

Long-term bonds had the single biggest draw down of -32% while stocks came in at -25%.

Medium-term bonds had a best single year return of 14%, which was less than half of the stock market’s best year of 31%.

Stocks created an additional $20,500 of wealth with a single $10,000 investment.

Closing Thoughts

Retirees should not flee to bond heavy allocations in an attempt to reduce the risk of losing money in retirement. Doing so would actually impair the portfolio’s total wealth creation relative to the risks taken.

While bonds returns are handicapped by inflation and don’t enjoy the equity appreciation stockholders receive in the market’s best years, they aren’t totally worthless either. The role of bonds in a retiree’s portfolio should be to help reduce sequencing risk. An ideal retiree portfolio looks something like this:

Cash and high yield savings for current year expenses

Bonds and high yield savings for years 2-5 expenses

Stocks for the remainder

Each year, we would rebalance the bond and stock allocations based on their current year performance to ensure enough cash for current year expected spending. Year-to-year fluctuations are minimized because we've already set up a diversified pool of high quality investments while never giving up the underlying stock engine delivering inflation beating performance over the long-term. The allocation decisions from year-to-year are highly variable and, as always, are ultimately a function of your spending habits and retirement goals.